What are the Japanese doing?

In March 1945, sergeant Wolfgang Hirschfeld makes a strange observation: While loading the submarine of U-234 in the port of Kiel, the Oberfunker sees two Japanese on a large box. They label packets with ink, and the sailors are then stowed away in the ship. Hirschfeld remembers later:

“The packets are about 25 x 25 cm in size, hammered in wrapping paper, glued together and heavy as lead. The inscription is ‘U 235’. When I asked what the packets contain, the Japanese, who is called Tomonaga, says: ‘Is charge of U-235. Don’t go to Japan anymore.”

Hirschfeld investigates: U-235 never had contacts with Japan. Did the Japanese lie to him?

His mistrust is justified, “U 235” does not mean a submarine. It is the abbreviation for Uranium 235 – the fissile uranium isotope from which nuclear weapons could be built.

High-ranking passengers, secret blueprints

As the end of the war approaches in Europe, the Nazi regime still wants to help allied Japan. Under the command of the “Marine Special Service”, responsible for secret missions, the minelayer U-234 is converted into a transporter: the mine shafts become storage spaces, additional tanks are supposed to guarantee a range of 18,000 nautical miles and the supply over nine months. U-234 gets a snorkel for long underwater trips and state-of-the-art radar technology to protect against airstrikes.

In addition, some high-ranking passengers are also on board, such as an air force general and experts in missile, naval and aircraft engineering, including Japanese officers Hideo Tomonaga and Genzo Shoji. According to the loading list, blueprints for rockets and aircraft such as the Messerschmitt 262 jet fighter are stored. And 560 kilograms of uranium oxide, from which about 500 grams of nuclear-capable uranium can be extracted.

But does Japan even have a secret nuclear weapons program in 1945, as US historian Robert Wilcox suspects? This has not been proven. Equally speculative remains whether U-234 will take a completely disassembled Messerschmitt 262 and components of the V2 rocket on its mysterious mission, as is often claimed.

The Forbidden Diary

Radio operator Wolfgang Hirschfeld has kept a secret and forbidden diary on submarine trips. His U-234 notes confiscated the Americans after the war. He reconstructed it from memory in 1947 and processed it in the book “Enemy Journeys: The Logbook of a Submarine Radiooperator”.

Some things remain vague, others cannot be verified. And yet Hirschfeld’s memories are one of the main sources of the activities of the two Japanese. Shoji is therefore a specialist in aircraft engineering, Tomonaga submarine engineer. He even brings a 300-year-old samurai sword on board:

” (The sword) was given in Kiel during a ceremony in the presence of Ambassador Oshima for the duration of the trip in the hands of the commander (Johann-Heinrich Fehler). In doing so, the Japanese have put their lives in his hands; they do not possess other weapons.”

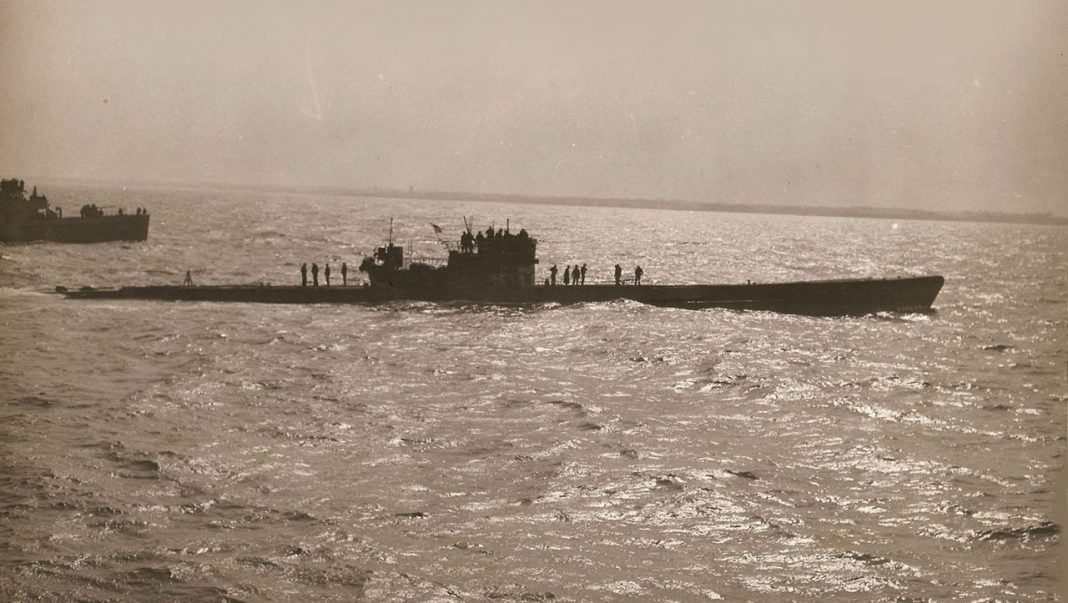

Heritage Images/ Getty Images

Hirschfeld reports on the chaos of conflicting radio messages when the submarine docked in the occupied Norwegian port of Kristiansand in April 1945 for repair. “U 234 has not yet been phased out. Wait for the command. Leader’s Headquarters.” Should Air Force Chief Göring still be on board, as is speculated? Naval Chief Dönitz decides that U-234 should “immediately expire at its own discretion”.

On April 15, 1945, the first and only enemy journey begins. The XB boat, 90 metres long and weighing 2100 tonnes, has never been used since it was hit by an airstrike.

For the first few days, the submarine dives almost constantly. The Allies are dropping sonar buoys so that their aircraft can drop water bombs more specifically. But U-234 goes unnoticed. Only once, diving in snorkeling depth, it almost rams a freighter in pitch-black night, as Hirschfeld writes:

“We’re just getting under the steamer. At any moment we fear that he will suck us up and shave off the tower with the screws.”

“The slogan is still called Japan”

This is everyday war. Tensions on board are rising as the war heads towards its finale. On May 4, 1945 – Hitler is already dead – the successor government under Grand Admiral Dönitz orders the end of the submarine war.

U-234 but continues to plough through the Atlantic Ocean. Communication becomes more difficult, the Allies have conquered the naval longwave transmitter “Goliath” near Magdeburg. From then on, the crew is dependent on reports of shortwave.

May 8, 1945: Germany capitulated. Submarines are no longer allowed to spark encrypted. U-234 should “continue to run or return to Bergen” in Norway, according to Hirschfeld’s memoir, according to an encrypted radio telegram. Captain’s mistake, however, does not want to reverse.

“The slogan is still called Japan. But then we take up a slogan from Reuter that says that Japan has severed its relationship with Germany. So our journey has actually become pointless. Dönitz urges the submarines to capitulate.”

Over the radio, the men soon hear orders that they find humiliating. Flak munitions are to be thrown overboard, torpedoes are to be rendered unusable. A black flag on the sea pipe is the sign of surrender – as if the sailors were pirates. Mistakes hesitate. Are the reports an Allied war list?

“Are they getting us done?”

11 May: The war in Europe has been over for three days, but you are not so sure on board. “Are they getting us ready when we come with this flag?” asks Hirschfeld.

“We haven’t reported anything since we left. No one can know if we still exist. (…) What really keeps us from going to Cape Horn and hiding in the South Seas on an island?”

Captain Fehler, however, is now convinced that the messages are genuine, partly because a German submarine confirmed them by radio. What is the point of hiding and later being convicted of war crimes? The Japanese are protesting. They assure that the Germans will not be interned in Japan. But mistakes want to capitulate.

On May 13, 1945, Hirschfeld calls the station in Halifax, Canada. The answer in English: “U-234, enter location.” The crew dyes a bed sheet black, attaches it to the sea pipe, but leaves flak and torpedoes ready for battle. She wants to fight if that is a trap.

Death struggle in the bunk

Meanwhile, the captain is told that the two Japanese are lying in their bunk, unconscious and roaring. Before that, they had said goodbye without anyone pointing it out. According to Hirschfeld, Tomonaga had given away his Swiss watches. Apparently they have taken an overdose of the sleeping drug Luminal and cannot be awakened by “strong shaking”, according to Funker Hirschfeld. In a sea bag a farewell letter:

“Let’s die quietly. Bury our bodies on the high seas.”

The Japanese also ask that their luggage be dumped in the sea with secret documents.

At the same time, a battle of nerves is underway over surrender. U-234 is located in the Atlantic Ocean, right between the Allied zones. Captain’s fault does not want to be taken prisoner by the Canadians and The British. So he’s heading for U.S. waters. Halifax sends an aircraft and demands a course correction. Hirschfeld must report an incorrect position to gain time.

The US destroyer “Sutton” intercepts the radio traffic and contacts U-234. Now, according to Hirschfeld, the Japanese are being buried.

“Now everything goes very fast. The corpses are laced into hammocks, which are provided with base weights on deck. Then comes the command: ‘Both machines stop!’ Ten minutes of silence on the bridge and in the boat. The Samurai Sword is added to Tomonaga.”

The Trail of German Uranium

A little later, the war is over for U-234. On 19 May, the “Sutton” arrives at Portsmouth Naval Base with the captured submarine. Hirschfeld and some officers are initially detained in prison, then they are supposed to explain technical details to the Americans aboard the submarine. What the label “U 235” means on the packages, Hirschfeld supposedly only becomes clear when the Americans run through the boat with Geiger counters.

On August 6, 1945, the United States dropped the atomic bomb “Little Boy” over Hiroshima, and three days later the second (“Fat Man”) on Nagasaki. To this day, the question remains whether a small part of the enriched uranium of this bomb originated from U-234 – did the Germans inadvertently accelerate the dropping?

Most experts now think this is conceivable, but very unlikely. It is true that the German uranium oxide ended up in a US nuclear research facility, which possibly extracted fissile uranium 235 from it. However, whether this material is directly used for the strictnuclear weapons programme cannot be substantiated. It would have been short in time.

U-234 certainly did not change the course of the war. In any case, the Americans had more than enough material to end the war in distant Asia by atomic bomb. Two years later, they sunk U-234 during a military exercise off the coast of Massachusetts.